The people of Custer County were enjoying the warm temperatures of September 1959, as were the nearly 10,000 head of cattle that were the primary source of income for the roughly 1,200 citizens. Ranchers were working at sorting and weaning calves and finishing up putting up hay for the winter. Only a few ranches had started to drive the herds out of the Valley along the three routes of Texas Creek, the Oak Creek Grade, or the Hardscrabble Pass. Sheep ranchers had mostly brought down their grazing flocks from above treeline in the Sangre de Cristos and were in the process of sorting the sellable animals from the rest of the flock. For all intents and purposes, the autumn season had been bountiful.

It was not until Sunday, September 27, that the Wet Mountain Tribune weather observer Marvin Rankin noticed that the pressure readings on his barometer had started to drop, but it did not overly concern him as it was not unusual for a quick little snowstorm to hit the Valley in early autumn. However, by Monday, it was clear to Rankin and many of the ranchers in the Valley that the storm was not acting like a quick little snowstorm; it resembled heavy spring snow.

All day Tuesday, ranchers worked to bring cattle closer to the home barns so that they could attempt to feed the enormous herds as the snow started to pile ever deeper. However, only a few managed to get the entirety of the herds home, and by Wednesday, it was all but impossible to wade through the several feet of snow.

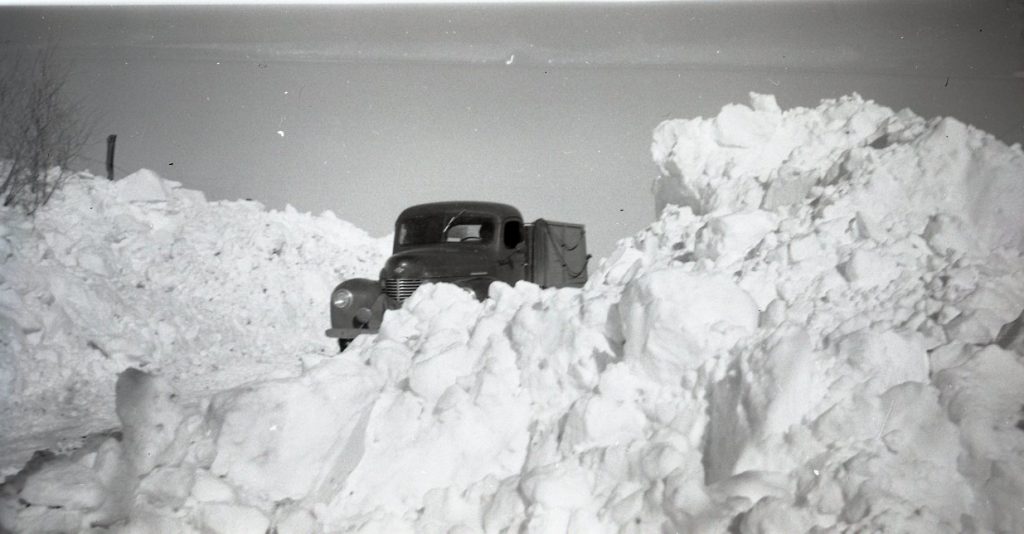

Road crews working for the county had been plowing nearly nonstop since Monday, using two of the new diesel-powered road graders, but by Wednesday, the equipment had broken down, and snowplows mounted on small trucks lacked the weight to push the wet and heavy snow. The small state highway road crew was also unable to keep up with the ever-increasing amounts of snow, and by Thursday morning, they were stuck in place.

Locals were still not overly concerned; the snow should let up soon, and so most just hunkered down. But the snow did not stop falling.

It was on Saturday morning that local businessman C.L. Canda, Jr. woke up to nearly 50 inches with no indication from the grey sky that the storm was going to let up. Fortunately, the power and phones had remained operational and, at this point, were the only connection to the outside world. Canda contacted J. Edgar Chenoweth in Trinidad, who was the Congressman for the Third District in Colorado. Hearing that a disaster had unfolded in Custer County, Chenoweth contacted Brigader General R.A. Risden, commander of Fort Carson, located 80 miles from Custer County outside of Colorado Springs, to ask for assistance. Understanding the immediacy of the situation, the General started to assign a task to enlisted engineers to dig out Custer County and its increasingly hungry herds of cattle.

After a declaration of disaster by Lieutenant Governor Rober Knous, the military convoy left Fort Carson along the narrow and winding county highways and roads toward Custer County. The contingent included several snow weasels, bulldozers, road graders, plows, and deuce and half trucks, along with 60 soldiers trained as engineers.

While the Fort Carson column was heading southwest, and unknown to the residents of Custer County, a separate convoy of military men and equipment from the Pueblo Ordnance Depot under the command of Colonel C.J. Murphy was working its way west of the town of Rye after digging out the small community there.

By 7 p.m. Saturday, Major Andrew Andersen arrived with his column from Fort Carson, and the teams worked to plow out a wide space to park the equipment. Locals coordinated with the soldiers, and about a dozen households housed and fed the tired men Saturday evening.

Fortune finally smiled on the Valley; Sunday morning, the snow had stopped, and bulldozers from the combined force of 75 men started to clear roads and widen areas for cattle, helping ranchers feed the starving herds.

According to Marvin Rankin, 55 inches of snow had fallen in Westcliffe, which carried 5.93 inches of water equivalent, which was the largest recorded snowstorm in the region at the time (The record held until Spring of 2003).

As the army units worked to clear the snow, locals started to survey the damage. The roof of the Canda Theater (now known as the Jones Theater) had collapsed, and many sheds in town had collapsed. Cattle and sheep ranchers reported that many of their barns had collapsed under the massive weight of the snow. Ben Kettle on the Valley floor reported nine collapsed outbuildings and one animal that was crushed in the collapse. Other ranchers were not so fortunate as they reported milk cows being crushed as the barns collapsed. Rod Canda, on the south end of the Valley, reported that between 35 and 50 head of his sheep had perished in a barn collapse. Later, military crews helped him dig out the dead animals in the feet of snow.

It was noted by the Wet Mountain Tribune at the time that while the cattle had lost condition, the actual losses were likely not going to be fully understood until the following spring. Because the storm came on so suddenly, most of the scrub oak and aspen trees had not dropped their leaves. With nothing left to eat, the cattle ravenously ate the leaves and pine needles. This type of grazing often poisons the animals, and if the cow is pregnant, it will often cause the calf fetus to abort but spare the cow. One odd but highly-detailed observation by local ranchers was that brand-new barbwire fences often snapped due to the weight of the snow. However, the old rust fences sagged but did not snap.

The disaster in Custer County made national headlines, and for weeks, helicopters buzzed the area, taking photos of the snow. Of course, this buzzing by the newly invented helicopters startled cattle, and rancher Ben Kettle complained bitterly about the stampede caused by the passing chopping machines.

In the end, the locals simply did what they always did, which was digging out, repairing the barns and roofs, and continuing on with their day-to-day lives.

– Jordan Hedberg

(A big thank you to Pam Camper for posting her collections of newspaper cuttings printed on page three, which inspired me to research this story. She remembered, as a small child, the soldiers eating dinner in her parent’s house and smelling horrible after pulling all the dead sheep from the collapsed Canda barn. In addition, a huge thank you to Dale Coleman, who found the pictures taken by his grandmother Celesta Adams on her Brownie Six Camera as crews cleared the roads on the Valley floor as pictured below.)