The legendary baseball coach Yogi Berra once said, “It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future,” and what is true in baseball seems to hold outside of the diamond as well. One of the joys of being a historian and purchasing a newspaper that is over a century old was the piles of old documents, photos, film negatives, and other assorted documents that had been collected for over 60 years by previous owners. While to the average visitor, these documents might seem little more than old curiosities collecting dust, to this author they are near-forgotten portals to the past so that we can see the world through the eyes of the people at the time. And one such recent document caught my gaze when I was looking for something else.

The document is a report by the Custer 2020 Partnership that was released and published in March 1996. The report aimed to predict what the region would be like in 2020, which was nearly a quarter of a century in the future. “Custer 2020 dedicates this research of Custer County to all the people who reside in the county as well as those who vacation and visit here. Custer 2020’s goal is that the research contained herein will help people understand Custer County better and, with this knowledge, work together to plan for the future of the area.”

The main author of the report was Dr. Ann Willson, a resident who still lives in Custer County. The report was completed with assistance from Professor Walt Hecox, a sustainable development expert who was part of the economics department at Colorado College. One of his students helped as well. Grants from the Colorado Trust helped pay for the research. The 46-page study is full of interesting history, facts, charts, and data points. But what is the most interesting 28 years later are the predictions of what Custer County would look like in 2020.

I have a thing for the topic of predictions. Much of it came from my love of history as great men and women throughout the ages made predictions and set their people on the path to greatness; or, at least, that was the hope of the great men who made those predictions. What was always interesting to me was how often those predictions proved to be wrong. For example, I had an obsession as a boy with the sinking of the Titanic, and in many of the books I read, there was an oft-repeated quote that always stood out when a newspaper interviewed the Captain of Titanic, E. J. Smith, shortly before it set sail on its first, and only, cruise across the Atlantic. “I have seen but one vessel in distress in all my years at sea. I never saw a wreck and never have been wrecked, nor was I ever in any predicament that threatened to end in disaster of any sort.” It was clear that the story aimed to tell the reader that the ship was indeed unsinkable and that the captain did not predict any problems on the maiden voyage.

When I attended Custer County High School in the early 2000s, the hot political topic of the school was the building of an addition so the school could deal with the swelling numbers of children that were enrolling in the K-12 system. Most of the middle school classes I attended were in modular homes that had been set up outside the main school building, with students trudging through the wind and the snow between classes. Several efforts in the 1990s had failed to convince locals to raise taxes to pay for bonds that would build an expansion of the school. What I remember from some of the discussions referred to a group called Custer 2020.

In the end, and I think with the help of the Custer 2020 Partnership’s predictions, the bond issue finally passed, and in 2002, high school students entered the new wing of the high school. The newly expanded school had been built to accommodate almost 1000 students K-12, even though enrollment was about 550 at the time the bond issue passed. By this point, it was commonly assumed in the community that the growth of the student population and the county would continue similarly as it had done for the past 12 years, a period which had seen almost a doubling of the population from 2000 to 3800 residents with an equally large growth in secondary vacation homes.

It would be unfair to single out the Custer 2020 group for being the source of the assumption that the county would continue to grow at such a fast pace. The entire State of Colorado, and much of the rest of the nation, was convinced that exploding growth in population, technology, wealth, and the economy was inevitable since the United States had won the Cold War in December 1991. Capitalistic Liberalism was a system that worked and had “won” in the half-century struggle against the communist nations of the USSR and China, and the people of the United States were reaping the benefits of having the “correct” system. The Custer 2020 report echoed much of the beliefs of the nation at the time, and it ended up biasing many of the predictions that came from the report.

The problem was not that the predictions ended up being wrong; it was that the community made bets and borrowed money on the predictions. Now, the county is facing losses on those bets, and because of borrowing and zoning restrictions, it is less flexible in dealing with a reality that is not as rosy as leaders had hoped back in 1996.

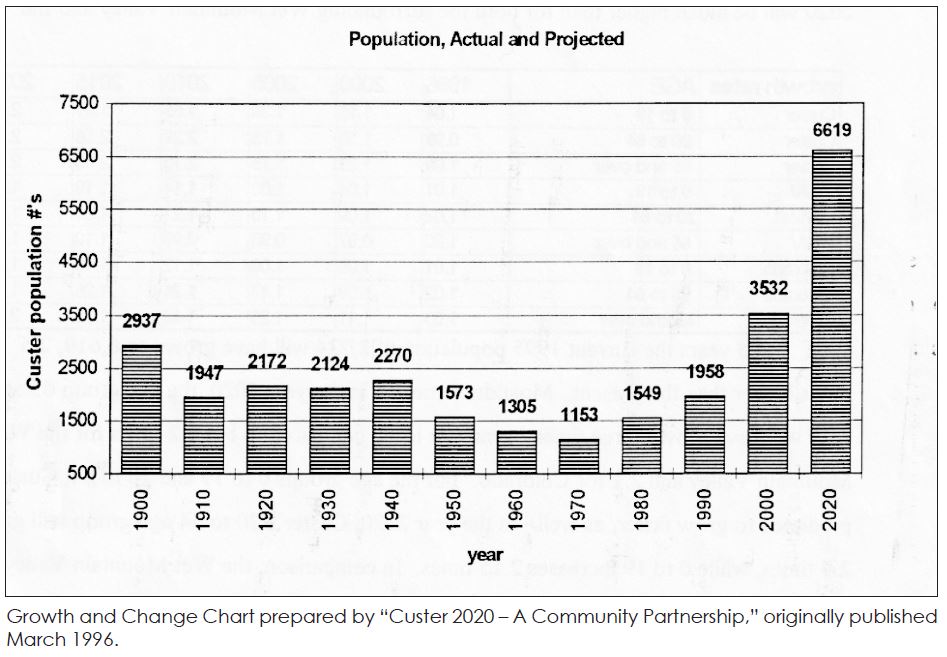

At the core of the Custer 2020 predictions was the future population of the county. According to the report, “The current 1995 population of 2,743 will have grown 2.5 times to 6,619 by 2020.” Further, the report stated that the growth of the demographics of the county would be roughly the same. Locals under 18 would grow at the same rate as those 18-65 and those above 65. This would mean that there would be almost 892 students by 2020 and that persons 65 and older would only be 979. That would leave a working age group of 4,748 people. None of this included the many secondary homeowners that accounted for 63% of all homes in Custer County in 1995.

When you read through old Tribunes through the last part of the 1990s and early 2000s, much of the political actions revolved around tightening up zoning laws and making sure that “sprawl” from the growth would not harm the pastoral feel of the region. After several large apartments had been built in Silver Cliff in the 1990s, the two towns quickly changed zoning laws, which prevented such density from taking place ever again and limited nearly all homes to single families with large lots. The county continued tightening restrictions, preventing additional units from being built on properties and restricting those who could live on a property to related family members only. Again, these actions were not unique to Custer County, and many of the regulations passed at the time just mimicked what Front Range cities were doing.

What is interesting is that for the first 12 years, the predictions made in Custer 2020 were reasonably correct. The student population looked like it would be on track to break 600 by 2010, and the population was growing locally. The growth of the school seemed to be actually going past the predictions, so another bond was issued to build a second gymnasium, which was completed in 2007. But then something unexpected happened: the Great Financial Recession of 2008.

“Except that something unusual happens—usually.” This was how Nassim Taleb, the expert on rare events, explained the regularity of the unexpected in predictions. It is hard for me to describe the changes that resulted from 2008. While the rest of Colorado was not hit hard by the crash in home prices, Custer County was devastated as much of the middle class was involved in housing and real estate in one way or another. Real estate sales dropped 80%, and home building almost reached a complete stop. For the next four years, middle-class workers left the region as it became clear that the housing boom would not return. The bottom of the market was in 2012, but the building and real estate markets did not fully recover until the unexpected boom in housing in 2020 resulting from the COVID pandemic.

It was a lost decade for Custer County. The population actually decreased from 2008 to 2014 and only started to tick up slowly in 2018. Student enrollment went from just under 600 in 2005 to 425 by 2019. Enrollment has continued to slide and is now at or below 300 students who occupy a building designed for 1000.

While the county population doubled from the time the report was issued in 1996 to 5,534, it was not distributed evenly across the board. Those 65 and older account for just under 2000 persons, double the amount projected, and the working-age population is half of what was expected. Even more stark is that in 1994, the Custer 2020 report estimated that the labor force was 1,267, and it is expected that it would increase to 2,000 by 2020. Instead, the 2020 Census shows that total employment is only 604, half of what it was in 1994, and total self-employed businesses were less than 200. Much of the rest of the working-age population commute to jobs in Fremont, Chaffee, and Pueblo Counties. This segment of the population has been rapidly decreasing as these families move away, looking for better jobs and more affordable housing, increasingly to the American South, such as Texas and the Carolinas.

What is most perplexing to me is that despite the reality that predicting has proven to be an abject failure, county and town leadership continues to predict. It is not just forecasting but continuing to believe that Custer County will grow into a large population center in the near future. The Custer County Commissioners tried to build a $31.5 million Justice Center and new jail in the region because it was assumed that crime would increase with a growing population. They ignored the fact that the group most likely to commit crimes, males between 16 and 30, had continued to fall in the overall population. After voters rejected the building, the Commissioners restarted plans to get it built the next year, with Commissioner Bill Canda stating, “We learned a lot from the failure last time; this time, we will make sure we do a better job with marketing.”

Every five years, the governments updates its “Master Plans,” which are essentially little predictions that are supposed to guide decision-making. The Town of Westcliffe has announced that they are starting to update their plan, and it is clear that Silver Cliff will do the same. In the plans are ideas for increased parking spaces, more sidewalks, and paved road improvements. It is doubtful that Westcliffe will realize that they continue to lose population and that such projects might just be bridges to nowhere.

In 1996, it would have been unthinkable that Silver Cliff would have a larger population than Westcliffe, but that is what happened. In 1996, it would have been inconceivable for the school football team to go from 11-man teams to barely being able to field a 6-man team, but that is what happened. Again, the belief that the population here will continue to grow is held by the rest of the state, including the State Demographer’s office. Even though 2020 blew up the predictions the State Demographers Office had made (Colorado had almost no population growth for three years), it insists that the population growth will recover to 1.5% per year for the next 15 years.

But despite the facts, it is likely the Custer County Government and the Town of Westcliffe (the Town of Silver Cliff has a much better grasp on reality) will continue to make plans for future growth and maybe even place bets on it with loans to build infrastructure that might end up serving ghosts.

– Essay by Publisher Jordan Hedberg