There was something unique about the rockslide that closed the intersection of Highway 96 and 165, known locally as Mackenzie Junction, as previously reported in the Tribune on Sunday, December 29. The narrow and winding highway from the junction to Wetmore is flanked on the north side by thousands of feet of vertical and exposed rock outcroppings. Every year, a few rocks slide or tumble onto the blacktop after large rainstorms or during the spring thaw.

However, when the highway is closed, it is because large boulders have broken loose and landed on the roadway. Sometimes, these boulders and the other rocks it jars lose on the way down are the size of a small house, and it takes considerable work to blast the behemoth boulders to manageable sizes. The overwhelming pattern on this stretch of high mountain highway is that large rocks work-lose and tumble in the form of a landslide.

But what happened on December 29 was a textbook version of a rockslide defined by geologists as: “rockslides are a type of translational event since the rock mass moves along a roughly planar surface with little rotation or backward tilting.” This is a precise way to say that part of the hillside gives way almost at once on a single plane of weakness. The video recorded by Sierra Wright, shown below, reveals that the whole hillside had already slipped several feet down, and the resulting pile of rock rubble toppled onto the highway.

This type of movement is not typical in the Wet Mountains as this range is comprised of fairly cemented-together layers of granite metamorphic rock. The layers are just too glued together to slide as a mass.

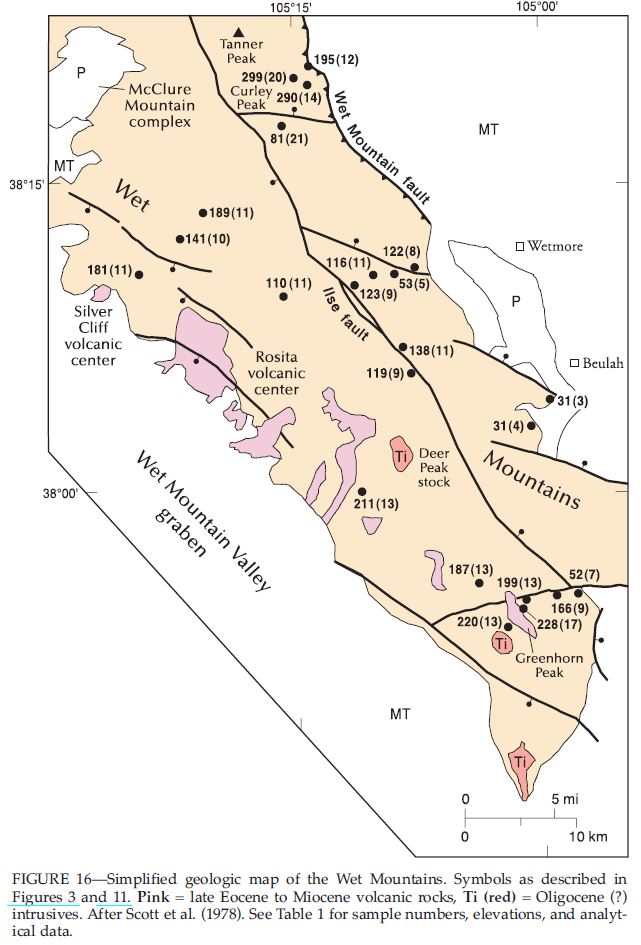

Fortunately, local Jay Temple quickly identified the reason for the unusual movement when he visited the site the day after the slide. Temple recently retired from the United States Geological Service (USGS) working in Colorado. There is probably nobody else in the Wet Mountain region who understands the local mountain geological history and structure better. In a phone conversation with the Tribune on December 31, he explained that a roughly 1.5 billion-year-old fault line, running from Rye to the edge of South Park, some 55 miles long and only about 200 yards wide, was the reason for the rockslide. Well, that, and also, the fault was exposed when humans cut through that hillside to build the Hardscrabble Road in the 1920s and 30s, and the cliff was made even steeper in 1991 when the highway was widened to add turning lanes onto Highway 165.

“This area of highway runs right through a fault zone known as the Ilse Fault. It is an ancient fault, and while it is not active anymore, it was active about a billion years ago. While it might settle occasionally, it is not an active tectonic fault.”

Tectonic faults are cracks in the earth’s surface caused by the movement of the crust of the earth. This earth movement on a human scale is mind-numbingly slow, and watching paint dry is the speed of light by comparison when taking in the 4.5 billion years of the earth’s life span. The Ilse fault was created long before the Rocky Mountains were pushed upwards 75 million years ago.

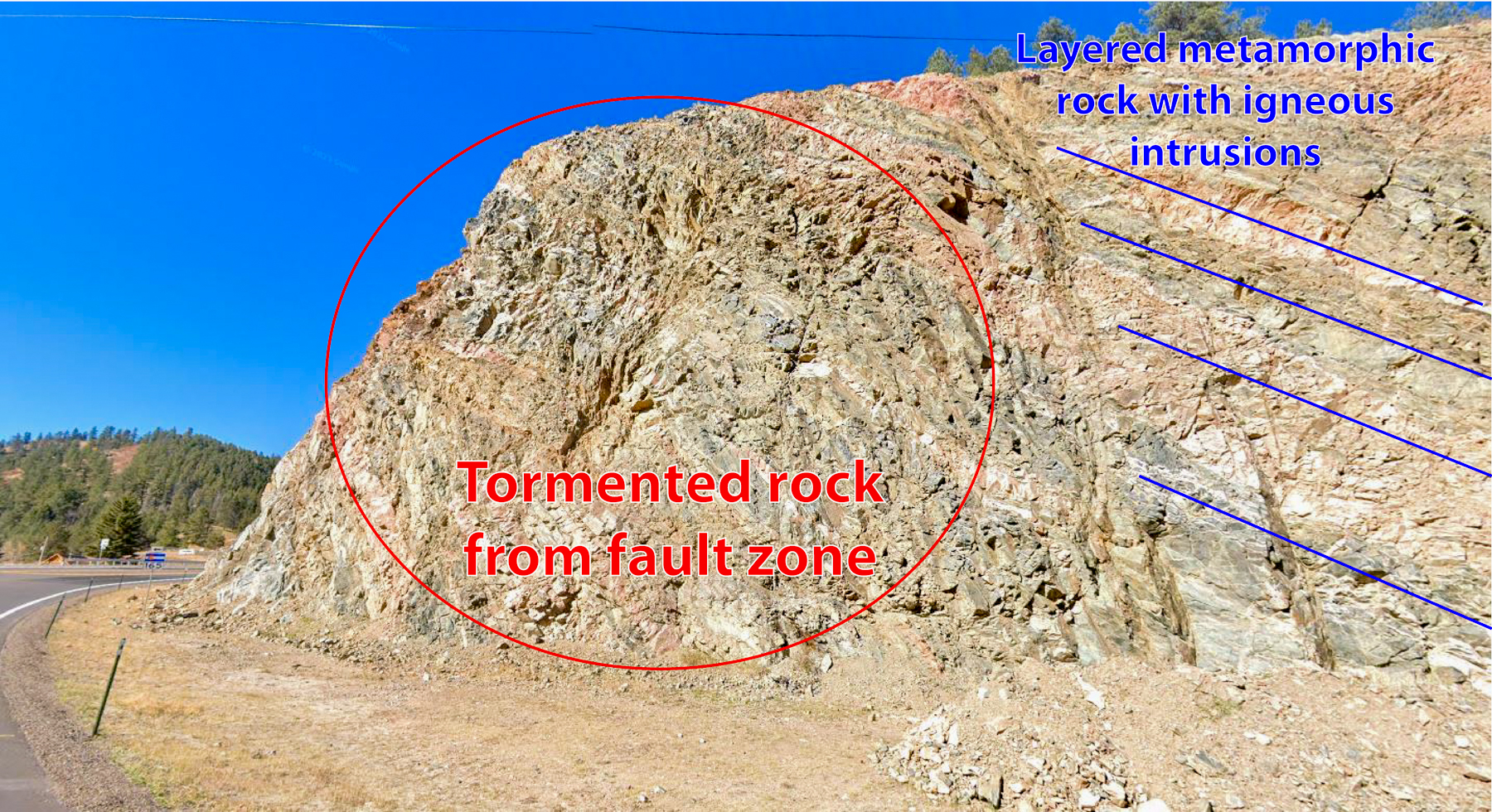

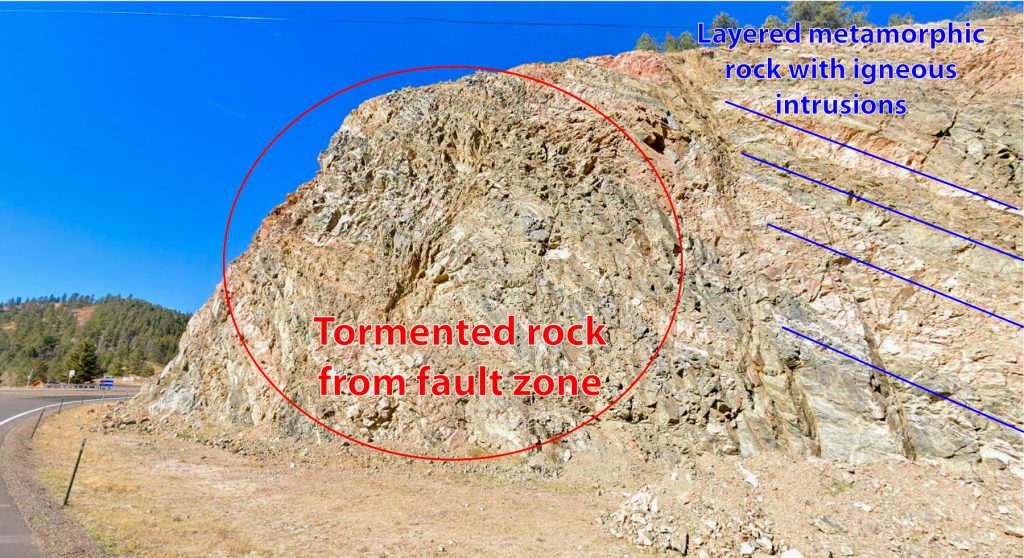

“So what happened at this location is that because you have a fault system running through, and with that main fault there will also be associated fractures on either side of the fault plane. So that movement will happen in one or two major planes, but associated with that and outward in both directions will be parallel fractures and micro faults that will occur.” Think of this as rubble being created between the fault, breaking the otherwise solid metamorphic rock into gravel bits compared to the large layered slabs seen when driving up the Hardscrabble canyon.

Temple entertainingly referred to the rubble created by the cracking of the ancient crust of the earth as “tormented rock.” However, the term seems fitting when looking at photos courtesy of Google Maps of the cliff face from 2023, before the recent collapse. As seen in the picture below, solid layers of rock are clearly visible, and the layers suddenly become more jumbled and less defined—an indication of the fault zone.

“This fault zone is going to accumulate a lot of water from snow melt as the water seeps through all the cracks and fractures. And because that water is going to go through the fracture systems, it will eventually gravitationally adjust itself.” Because of the cliff over 100 feet high that was created when the road was widened in 1991, those water-filled fractures will move the hillside downhill.

Temple pointed out that only a tiny part of the unstable fracture zone had collapsed on December 29. “At some point, this will happen again. The only way to solve the issue is to lower the grade of the slope through explosives and rock removal.”

The extremely wet fall and heavy snow in November have since melted on the southern-facing slope. The water on the surface cracks and freezes, and that ice expands. When the ice thaws, it leaves a weakened and further cracked rock. Known technically as cryofracturing, this process, plus the recent warm temperatures, was the straw that broke the back of this billion-year-old weak point.

Such events rarely come without predecessors. On July 16, 2018, a much smaller slide at the same spot caused the highway to close briefly after floods hammered the Wet Mountains. This part of the highway was widened in 1991 in a major project at the junction of 96 and 165, a story the Tribune will publish in the next few days. According to locals at the time, the slope was much less steep and the crews assumed the rock was a solid as other parts of the pass.

As of this writing on December 31, the rubble had not been cleared as crews had started making sure the slope was safe to work under and starting to remove the rock. The Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT), along with Langston Excavation, were working through the New Year’s Holiday. Highway 96 and the Junction of 165 to Rye are now open, but east of the intersection, the highway remains closed through the Hardscrabble with no estimates of when it will reopen.

Of course, Temple reminded this author that the Ilse Fault had other histories in the region, “it’s the same fault that allowed lead carbonite, zinc, silver, and some gold to accumulate as deposits. The ghost town of Ilse, just 5 miles northwest of Mackenzie Junction, was a fairly major mining operation in the region from the 1890s until the 1940s.” To read more about the history of the former town of Ilse, read this excellent piece by local writer Hal Walter by clicking here.

The Tribune will continue to update the public on the rock removal and repair of the highway.

Jordan Hedberg