The “Star of Bethlehem” is an iconic presence in the Christmas holiday season, and has been for almost two millennia. Whether in religious or mass cultural observance, during Christmastide the star referred to Biblically only in the Gospel of Matthew (2:1-2, 9-10) hovers over crèches, decorates wreaths and trees, and has thousands of iterations in both fine art and commercial art, including Christmas cards.

It would be hard to quantify the serious academic books and articles devoted to the Matthean account of a star associated with the birth of Jesus. Then there is additional literature driven by missionary zeal to convert the reader to a particular religious commitment. The total figure of publications is perhaps astronomical!

Speaking of which, astronomers who concede that an actual celestial phenomenon may be referred to in Matthew’s narrative, sometimes weigh in on what the “star” might have been. In order to do so, these scientists intersect their studies and suppositions with both ancient and modern historians of the late BCE and early CE decades—the range of years within which most scholars agree Jesus of Nazareth was born in Bethlehem. We do not know a date; December 25 is either a fourth century ecclesiastical convenience co-opting winter solstice and the Roman Saturnalia, or an earlier patristic juggling of Passover dates, during which time they imagined Mary was miraculously impregnated. In any case, after Puritanical bans on pagan Christmas practices, America did not recognize December 25 as a holiday until 1870. But we digress…

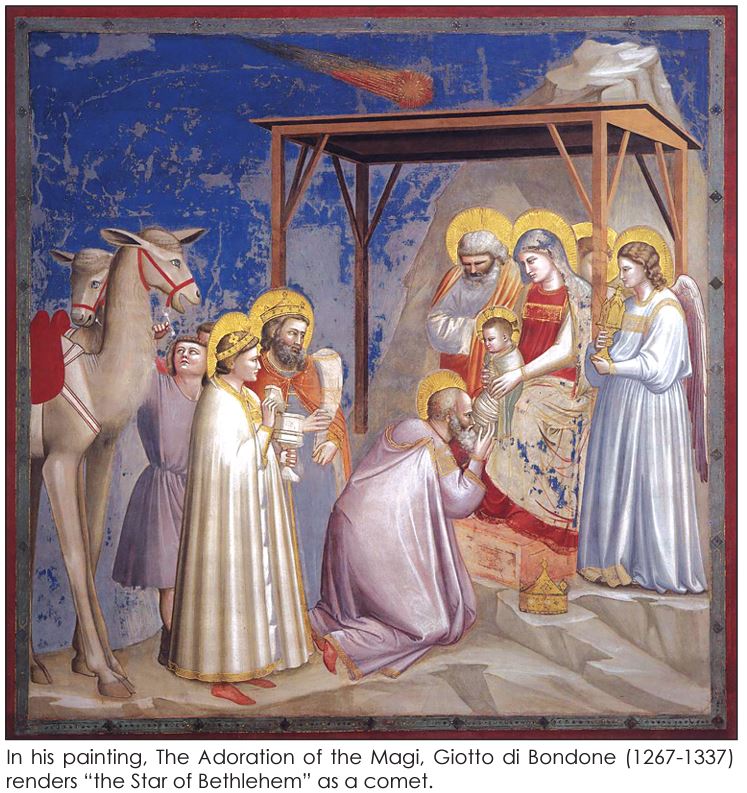

The astronomers findings are intriguing, but inconclusive. Some of the proffered contenders for being designated the “Star of Bethlehem” have been dismissed. It could not have been Halley’s comet, attested by ancient astronomers to have been in the vicinity in 11 BCE. The comet would not have led anyone, let alone the Magi, in a straight line, as its path, or position, changes with the Earth’s rotation. Besides, in the intertwining of astronomy with astrology in those days, a comet was a bad omen, not a sacred one.

Nor, astronomers agree, could such a star have been a nova or supernova. Had the Magi attempted to follow such a “heavenly” light, they could not have travelled in any semblance of a straight path from say, Babylon to Jerusalem to Bethlehem; rather, they would have navigated in circles—and they knew better than that.

The remaining two possibilities are interesting, and although speculative, the second is occasionally “testable” in the Valley’s December nightscape. The first is simply a story we could choose to tell about a story. In Matthew’s narrative, the Magi stop in Jerusalem to inquire of Herod. Why? The answer is hypothetical: again, given the fusing of astronomy with astrology in that time, these astrology-driven Wise Men astronomers could have been checking out the current court astrological interpretation of the heavens. Not certain of where they were going, they consulted with the local professionals. A nicely crafted story, but just that.

Yet even this imagined story begs another question. Why were these travelers interested in heavenly, or astronomical, events at all at this time? Astronomers who follow and contribute to this discussion point out that in April of 6 BCE, Jupiter, the planet astrologically associated with royalty, was making a fuss in the heavens, as the Moon was passing it in the constellation of Aries. The event could have been interpreted as portend of a royal birth in the area of this viewing. Again, a “could have…”

However, astronomer Michael Molnar, in his 1999 book The Star of Bethlehem, suggests that a planetary conjunction—the apparent meeting of two or more celestial bodies meeting in the night sky—indeed could have led the inquisitive Magi, as this type of astronomical event can continue for nights on end: one could “follow” it in a specific direction.

In follow up commentary, Grant Matthews—kind of campy to have a Matthews involved—professor of theoretical astrophysics and cosmology at Notre Dame, notes that the April, 6 BCE activity of Jupiter, mentioned above, also engaged Saturn and the Sun, as well as the Moon. If the Nativity star were the result of a conjunction, this particular one satisfies a number of other factors. For example, the conjunction occurred in the hours before dawn, and a later biblical rendering refers to Jesus as “the offspring of David, the bright morning star” (Revelation 22:16). Also, it seems the Magi lost sight of the star, which can be accounted for by Jupiter’s retrograde motion. Matthews points out, “Normally, planets move eastward if you’re following them in the sky. But when they go through retrograde motion, they turn around and go in the direction that the stars rise and set at night [westward].”

Matthews proposes that this April, 6 BCE conjunction harmonizes more with St. Matthew’s account than the June, 2 BCE conjunction of Jupiter, Venus, and the star Regulus in the constellation Leo, or the other 6 BCE conjunction of Jupiter, Saturn, and Mars in the constellation Pisces.

The “test” of this hypothesis here in the Valley can be our eye in certain Decembers, accompanied by an open mind, observing Jupiter, Saturn, and the Moon as they were in that April, 6 BCE sky. This year, little Mercury is at play in the pre-dawn skies, and Jupiter is having quite a display, neither sufficiently bright enough though to be in the running for the “Star of Bethlehem.” (By the way, if the nights are too chill for your stargazing, the interactive star maps at dateandtime.com can be pursued from the comfort of your armchair and laptop. Simply type in Westcliffe, CO, scroll down to the month and date you want to “see,” then go back to the map and click on what objects your interested in. Kind of cheating, we suppose, but akin to the Magi seeking out a court astrologer?)

Bright phenomena in the night darkness were intriguing in a particular manner more than 2,000 years ago, when the only light available was fire. In the Valley, we are blest with dark skies still, and just like the Magi, our imaginations can wander—which term, by the way. the ancients used to refer to the planets, the Wanderers.

I appreciate though, the way Matthews concludes his musings: “Nothing in science is ever case closed, nor is it in history. We may never know if the Star of Bethlehem was a conjunction, astrological event or a fable to advance Christianity. Maybe it was simply a miracle.”

A blessėd Christmas season, while you enjoy happy viewing!

– W.A. Ewing