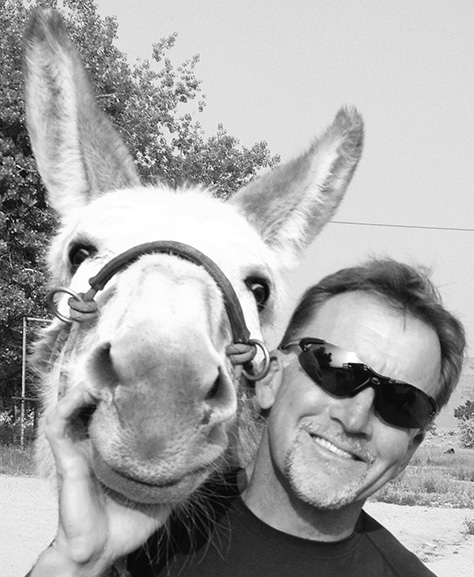

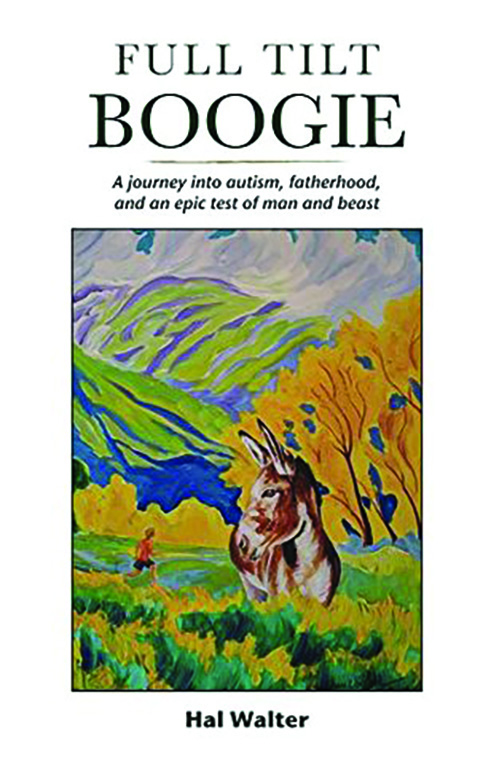

By Hal Walter

“I wanted you to see what real courage is . . . It’s when you know you’re licked before you begin but you begin anyway and you see it through no matter what. You rarely win, but sometimes you do.”

— Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird

In the fresh moonlight she floated on a loose rope like some strange creature out of a dream, part “racehorse,” part moonbeam. Her long ears trailing shadows on the gravel, and her sleek form slipping softly through the night air. Not exactly of this world. A locomotive with a heart and 10 million years of selection, both natural and supernatural, she was everything the past had conspired to bring to this moment and in the balance of her very being, everything her future held.

In the summer of 1986 Mary and I were engaged to be married. We’d been together as a couple on and off, but mostly on, since meeting in college as freshmen eight years before. The engagement was short and Mary’s parents would not accept any marriage unless the ceremony was performed by a Catholic priest. I really had no problem with that — someone had to do it — except there was the matter of the church’s required marriage classes which I refused to attend. After some gnashing of teeth by the family and discussion with the parish, and since the family was prominent in the church, it was decided that a couple of sit-down discussions with the priest would suffice.

We met with the priest in a small windowless room at the church. He told us of the meanings and challenges of marriage and then went through the process of explaining the ceremony, and the questions that would precede the vows, at last reaching the one question that truly mattered to the church.

“Will you accept children lovingly from God, and bring them up according to the law of Christ and his Church?”

He looked at me and then at Mary and then back at me. There was silence.

“No,” I finally said. “I don’t want to have children.”

The priest looked down and chuckled, as if he’d heard this same line from so many young men before me. He sat back and clasped his hands before him. I wondered if the wedding actually might be off after all.

“Well,” he said, “could you just say you would accept children lovingly from God on this day?”

My mind swirled as I thought deeply but quickly about the absurdity I believed organized religion to be, not to mention the irony of using literary license in dealings with God, who surely had the ability to get to the bottom of such matters. The double, maybe even triple, entendre played over and over in my head as I thought it over. “Would you accept children lovingly from God on this day?”

“Sure,” I said. “OK.”

• • •

On the last Sunday of July, 2012, I was bounding over and around rocks and boulders, racing down Mosquito Pass in the 64th World Championship Pack-Burro Race. My eyes, brain, and legs were quickly and carefully — and almost unconsciously — planning each step a split second before setting my feet, while simultaneously guiding my burro Laredo over this rugged terrain. We had made it to the summit of the 13,187-foot pass, neck and neck with George Zack and his burro Jack, and now with about 10 miles left in the 29-mile race it had come down to these two teams and the pace was picking up.

After rounding a sharp right switchback I drove Laredo ahead to take the lead, and suddenly I tripped on a rock and pitched forward toward the roadbed, flying, turning, tucking my head and landing on the back of my head and left shoulder. The rest of my body flowed and flipped with the momentum and landed with a whump — a complete somersault onto the rocky roadbed. I held tight to the lead rope and was dragged a short distance with my right elbow auguring into the road before finding the presence to spit out the word “whoa.”

Laredo stopped in his tracks.

George stopped too. He asked if I was OK and handed me my sunglasses, which had flown during the fall. I picked myself up, assessed the damage, and made my adrenaline-quavering legs start to work again. A short distance ahead was a checkpoint where I overheard spectators talking about moose and looked up to see two huge dark shapes wallowing in the willows, unaware of the human and equine drama unfolding on the road nearby. I was psychologically shaken and I wondered if I’d hit my head. Blood was oozing through my shirt from my shoulder. My legs now felt like they belonged to Gumby, and Laredo seemed more like Pokey than the burro that had taken the lead just a few moments ago. Over the course of the next few miles, I watched from behind as George and Jack gradually pulled away, and then disappeared out of sight. A couple hours later I finished a solid half-hour behind them in second place.

Just getting to the point where I’d taken that spectacular fall had required months of training and preparation, not to mention more than three hours of actual racing itself. In a split second it was over. I had won the race six times previously and at 52 years old felt as if my last chance to win another World Championship had just been literally dashed upon the rocks. I wondered how many races could possibly be left in me. Laredo, despite having won the race two times before, was also no longer at the top of his game. Besides, I had other major issues looming in my life, including a career in journalism that had become almost as big an anachronism as this crazy sport, and a son with autism. Back home awaited another year of scrabbling for a meager living, another year of struggling through each day of frustration, noise, tension and anxiety. And all the self-doubt and questioning that goes along with it.

Copies of Full Tilt Boogie are available at the Tribune office or on amazon.com in both paperback and Kindle versions.